Here is the longer version of the previous article:

Aviation Week & Space Technology May 06, 2013 , p. 36

Paul Kallender-Umezu

Tokyo

Japanese space programs face strict new reality

Et Tu, Tokyo?

The first order of business for new Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) leader Naoki Okumura will be to reorient his nation’s space program from advanced development to activities that may produce some commercial return on investment.

Based on the latest five-year “Basic Plan” for space promulgated by the Office of National Space Policy (ONSP), the new direction is putting pressure on JAXA to cut, postpone or reduce to research and development some or most of the agency’s flagship science, technology and manned spaceflight programs.

Based on the latest five-year “Basic Plan” for space promulgated by the Office of National Space Policy (ONSP), the new direction is putting pressure on JAXA to cut, postpone or reduce to research and development some or most of the agency’s flagship science, technology and manned spaceflight programs.

Some or all of the satellites planned for the Global Earth Observation System of Systems, the HTV-R pressurized sample-and-crew-return mini-shuttle and the H-X/H-3 launcher programs could face cancellation, concedes JAXA’s Hiroshi Sasaki, senior advisor in the strategic planning and management department.

“For 20 years, so much money has been spent by JAXA [and its predecessor, Nasda] on R&D, but there has been very little commercial return,” says Hirotoshi Kunitomo, ONSP director.

Under legislation passed last year, JAXA policy is now controlled by the 23-member ONSP, which was created at the end of a process begun in the middle of the past decade to wrest control of space planning from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), which controlled 60% of Japan’s roughly 350 billion yen ($3.75 billion) annual government space budget through its oversight of JAXA.

With a charter for change, ONSP reports directly to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who has final say over which of JAXA’s programs are funded. In turn, ONSP’s Basic Plan resets Japan’s space policy to three mutually reinforcing goals: promoting national security; boosting industry; and securing the country’s technological independence for all major space applications from reliance on foreign agencies—providing this supports the first two goals.

Kunitomo asserts that ONSP will continue to support frontier science as a lower priority, as long as it is based on the sort of low-cost, high-impact space science designed by JAXA’s Institute of Space and Astronautical Science , embodied by the Hayabusa asteroid sample-return mission. But former high-priority goals to promote environmental monitoring and human space activities and put robots on the Moon now have been moved down the list and must fight for funding, Kunitomo says.

Instead, only one of the three ONSP core programs—Japan’s launch vehicles—is run by JAXA.

The top-priority program, run by the ONSP, is to build out the Quasi-Zenith Satellite System (QZSS), Japan’s regional GPS overlay, with a budget approved for maintaining a constellation of four QZSS satellites by around 2018. A post-2020 build-out to a seven-satellite constellation will then give Japan its own independent regional positioning, navigation and timing capability.

The second is the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (Asean) newly sanctioned disaster management network run by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). This requires a constellation of Earth-observing satellites equipped with X- and L-band radar and hyperspectral sensors to monitor Southeast Asia. Japan will provide at least the first three satellites, with more funding through foreign aid packages. Vietnam has signed up for two X-band satellites. The system’s once-daily global-revisit policy requires a minimum constellation of four satellites that will need to be replenished every five years or so.

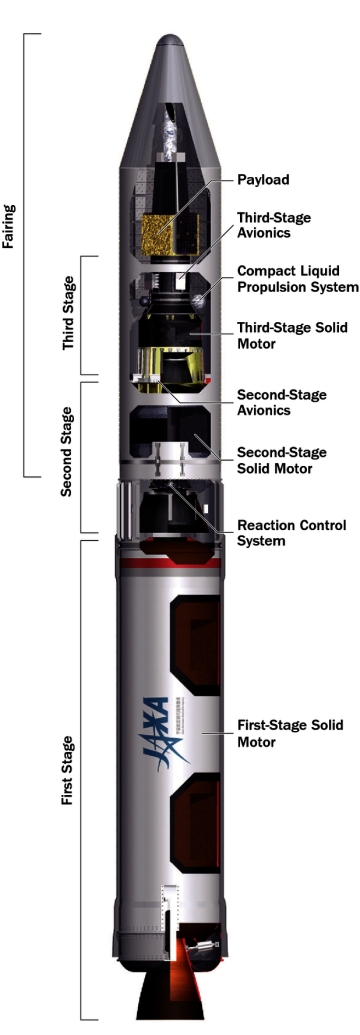

The third priority has JAXA focusing on improving the current H-2A launch vehicle in partnership with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) while continuing improvement of its new low-cost, launch-on-demand Epsilon solid-fuel rocket for smaller payloads. A variant of the Epsilon will be uprated to around 1,800 kg (3,970 lb.) from 1,200 kg to low Earth orbit, matching that of its predecessor M-V launch vehicle.

JAXA projects that fall outside the Basic Plan’s goals but already were funded for development will continue if it would be counter-productive to stop them, says Kunitomo. These include launching the upcoming ALOS-2 land-observing system and the Global Precipitation Measurement/Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar satellites. The Greenhouse Gases-Observing Satellite-2 (Gosat-2) will also continue, as it is funded by the Environment Ministry, not MEXT/JAXA.

But under a Feb. 25 budget plan drawn up by Kunitomo, several programs face close scrutiny, including the HTV-R sample-return mission, any future launches of the HTV-R transfer vehicle beyond the current seven planned to 2016, lunar exploration and all of JAXA’s follow-on environmental missions.

The ONSP’s logic for reauditing the HTV-R is harsh. As it is too expensive to commercialize, the H-2B will be ditched as dead once its HTV duties are finished. The HTV’s only purpose is to service the International Space Station, and Japan must minimize its costs, so logically the HTV, HTV-R and H-2B have no future beyond 2016 and the HTV’s seventh flight. Indeed, one industry official tells Aviation Week that Japan may launch at most two post-2016 missions.

The Basic Plan mandates that the agency’s already-low-priority environmental-monitoring programs undergo a “focus and reselection process.” This means the proposed GCOM-C, EarthCARE cloud radar mission and ALOS-3 electro-optical missions , the second main plank of Japan’s flagship international cooperation programs with NASA and the European Space Agency , will struggle for funding, and not all will make it, says Kunitomo. But a reconfigured ALOS-3 that can adapt to the Asean disaster management network at a fraction of its projected price would be more acceptable, he concedes.

As for the putative H-X, Kunitomo says ONSP questions the need to spend $2 billion and 8-10 years to develop it. JAXA and MHI say the program requires a launch system that no one can guarantee will be commercially competitive.

Industry’s reaction to all of this appears to range from stress to relief to anxiety. Masaru Uji, a general manager at the Society of Japanese Aerospace Companies, says QZSS and Asean network programs will provide steady, long-term business for Japan’s two satellite integrators: Mitsubishi Electric, which is supplying its DS2000 bus for the QZSS; and NEC Corp. , with its METI-funded 300-kg-class multipurpose Asnaro bus for the network.

The aerospace trade association figures show that for 2011, Japan’s total space sales—both overseas and domestic, and including all subcontractor revenues—amounted to only ¥265 billion ($2.7 billion). That is down from a peak of ¥379 billion in 1998, with overseas commercial sales accounting for only the low teens in revenue and JAXA programs taking the lion’s share of domestic business.

The Basic Plan “is moving in the right direction. You can’t build a business without infrastructure,” says Satoshi Tsuzukibashi, director of the Industrial Technology Bureau at Keidanren, Japan’s most powerful business lobby.

Uji is particularly pleased for NEC, which has been awarded a so-called private finance initiative to develop the QZSS ground segment, spreading steady payments to the company for at least the next 15 years. Anticipating the Basic Plan this January, NEC announced a ¥9.9 billion investment in a new 9,000-sq.-meter (97,000-sq.-ft.) satellite facility in Fuchu, west of Tokyo, to build a fleet of Asnaro satellites, which it also hopes to market commercially under the Nextar brand, says Yasuo Horiuchi, senior manager of NEC’s satellite business development office.

Similarly, Mitsubishi Electric said in March that it completed a doubling of its satellite production capacity to eight buses annually at its Kamakura Works. Having already sold four of the 13 DS2000-based satellites to commercial satellite services customers, increased volume spurred by the QZSS program will create further efficiencies and cost competitiveness, says Executive Director Eiichi Hikima.

MHI may face a different challenge, however. Ryo Nakamura, director of H-2A-2B launch services in the company’s Space Systems Div., says an improved H-IIA may gain one commercial contract in 2015-16. This may convince ONSP to fund the H-X (or H-3), whose first stage was supposed to use an LE-X engine with a high-thrust expander bleed cycle. Before the Basic Plan , the rocket was slated in JAXA’s road map to undergo the first of its three test launches around 2018. Hidemasa Nakanishi, manager of strategy and planning at the Space Systems Div., thinks it is Japan ‘s duty as an advanced spacefaring nation to complete its participation in the International Space Station, thus learning pressurized return technologies through the HTV-R .

JAXA’s Sasaki points out that nothing has been cut yet, and JAXA is going to battle to preserve as much of its “traditional” programs as it can in the relevant subcommittees though the spring. Key decisions will come in June.